Institutionalisation of Gender Pay Gap

The ‘gender pay gap’ has been brought back into attention with the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences being awarded to Claudia Goldin who has worked half a century of her life to understand this anomaly. The Harvard Economist was recognised for her research that showed that women are, on an average, paid lesser than men, even when they have higher education levels, and such gap in remuneration begins at a time when a woman gets married and increases when she gives birth to children.

This article looks at the research done by Claudia Goldin on gender pay gap in the US, and what this research can mean for the women in India, who face double-burden of livelihood and domestic work, combined with gender discrimination they face in both education and employment.

Claudia’s Work on Gender Gap

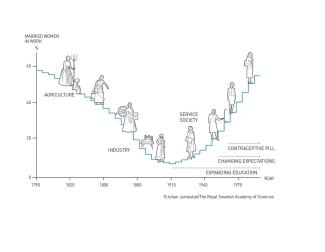

Based on two-centuries worth of data in the United States, Claudia has found that the labour force participation of a woman and her remuneration is determined partly by her individual decisions, and partly the broad socioeconomic changes. In her book titled ‘Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey Toward Equity’ (2021) she states, “Time is a great equalizer. We all have the same amount and must make difficult choices in its allocation. The fundamental problem for women trying to attain the balance of a successful career and a joyful family are time conflicts.” She says that men are able to have a family because women are stepping back from their careers to provide more time to raise a family; however, both men and women are deprived in this process, where men forgo time with their family and women forgo their career. However, it is most often than not women, who are termed primary caregivers in a family, who bear the cost of giving up on their careers, and prioritise rearing a family.

With the evolution of the American economy from agriculture to manufacturing to service sector, she noted that women were excluded from market activities, as the economy progressed from home to factories. In her work, Claudia found that post the 1970s, when the access to contraceptive pills became easier, it helped women plan their careers better by delaying marriage and child birth – just long enough to lay the foundation of a sustaining career. With an increase in child-bearing age of women and the time of their promotion at work through their career work, which phase began to come alongside each other, women were yet again forced to make a choice between her career and having a family.

Her work brings to light that no matter how qualified women are or how capable they are of handling high-profile jobs, they will continue to be held back in their career development due to her role as a caregiver. Unless the role of care-giving becomes gender-neutral, where participation of men is increased in household work and childcare, as well as reshaping work and social environments to attain work-life balance for both men and women, such pay gaps will continue to exist.

Gender Gap in India

Although her work is predominantly based in the United States of America and talks about women’s careers in formal employment, the concept of gender pay gap should be viewed universally, which is further complicated by race, caste, and other identities. Therefore, the work done by Claudia becomes extremely important in the context of India, where the main reason for gender gap is not only due to the patriarchy women face at home or in workspaces, but also due to caste.

The connecting thread between Claudia’s work and the situation in India could be understood by taking into account the institutionalisation of unpaid or lowly paid labour of women as an extension of unpaid care labour provided by women. The existence and social acceptance of gendered and unaccounted care labour is reflected in the way certain work are treated by government policies. It is a reflection of all encompassing patriarchal structures.

In India, we see that women are prevented from receiving good education and even employment in the formal sector. Reasons attributed for women not being allowed to seek employment is most often that the family has to maintain a social status. Therefore, even when women are qualified for jobs, they will stay out of the labour force. The surveillance faced by employed women in their households and non-participation in financial decision making in families is an additional cause for concern.

Despite these restrictions placed on women, the probability of women’s employment increased in households that experienced sharp negative incomes during the pandemic (Ishaan Bansal & Kanika Mahajan, 2021). However, this improvement was only transitory in nature and women were asked to step back from work once the economic situation in their households improved. Therefore, this showed that women’s labour often acted as an insurance during low-income periods for poorer households.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) conducted by the Union Government shows that only 29.40% women are part of the labour force in India, as opposed to 80.70% men (data from PLFS July 2021 to June 2022). The labour force participation of women has rapidly declined from 42.70% in 2004-2005, to this mere 29.40%, showing that women are withdrawing from the workforce despite rapid economic growth during the same period (an average of 6.8% GDP growth annually). It is seen that more than 90% of the 29.40% women are employed in the informal sector, including domestic work, agricultural work (mostly landless peasants), beedi and cigar rolling, construction work, street vending, among other such work. Moreover, 60% of these women are self-employed.

In the recent past, we have seen huge protests from women workers across India, who are seeking for better working conditions, better wages, etc. The millions of scheme workers who run basic services of the government like primary health, child care and nutrition are mostly women workers. In the name of volunteering for the society, these workers have not even been brought under the purview of labour laws. They survive on honorarium and are denied minimum wages. Millions of domestic workers who sustain families of relatively high earning households are denied basic protection from economic and gender exploitation. There is no law to guarantee minimum wages for them. They survive on the meagre amount that households pay them. Sanitation workers, who are predominantly women and workers belonging to the Dalit community, have been oppressed for decades at the hands of garbage contractors. They have been fighting for permanent jobs, wages on par with permanent workers, against sexual harassment at the workplace and caste atrocities at the hands of their employers. Garment workers which is a sector dominated by women workers on factory floors, have been fighting for better wages and working conditions. The garment workers protest in Bengaluru over change in EPF policy by the Modi Government in 2016, was unprecedented and showed the dependency of the workers on social security benefits.

In the construction sector, where women are employed alongside men, we see that women are restricted to doing head-load work or ‘beldari’ jobs, which involves fetching and carrying construction materials. This is, of course, considered as ‘unskilled’ work, and thus pays lesser than ‘skilled’ work of masonry, where majority of them are men. Women are double-bound by the construction work and the job of care-giving as full families are generally employed on construction sites, and we see children on site as well.

For these workers, where a majority of them are women, gender-based harassment, including sexual harassment, is a real hindrance in their full participation at work.

The recently released ‘Oxfam – India Discrimination Report 2022’, states that pay gap in India is a result of mult-faceted discrimination. Whether it is women or those belonging to historically oppressed communities such as Dalits and Adivasis, along with religious minorities such as Muslims, these workers continue to face discrimination in accessing jobs, livelihood and agricultural credit.

Labour Codes & Women Workers

To exacerbate the gender gap in employment, the four labour codes promulgated by the Union Government have launched an all-out attack against women workers in India. From permitting night shifts for women, taking away creche facilities in all sectors, and reduced maternity benefits, the labour codes have launched an assault on equal remuneration as well. The Labour Code on Wages, which has subsumed the Equal Remuneration Act, has removed the spirit of the legislation which upholds equality in payment of wages, thus opening up space for unequal payment of wages based on gender. With contract labour becoming rampant in essential services like sanitation work, service sector, where women dominate the sector, this system perpetuates bonded labour practices.

Conclusion

The fight for gender justice has been waged for centuries, where an integration of gender-based struggles are being combined with working class rights. Be it the struggle for women’s suffrage in the 19th century, where women joined labour unions, held strikes for higher pay, and protested for better working conditions, so that working women saw the right to vote as a way to gain more political power; or the fight for eight-hour work led by women garment workers in Chicago in 1909, women have to lead the way against the labour codes and fight for gender equality.

Today, it is evident that women are being treated unequally in terms of the evaluation of their labour. The institutionalisation of underpaying women’s labour must be challenged with all strength.